Widgets: Building Blocks For Flutter Applications

As you may have heard, everything in Flutter is a widget – from things that you can interact with on screen like buttons and text fields to things that you don’t interact with such as padding and margin. I once read an article where someone said after hearing that everything in Flutter is a widget over and over again they started to wonder if they were not a widget as well. In this post we are going to talk about Flutter widgets, the two types of widgets, examples and when you should use them. This is going to be a relatively short read.

Widgets

In Flutter everything is a widget – let it sink in. This statement was a bit confusing to me when I started working with Flutter. However, after a few days I saw how brilliant this idea was. Everything being a widget makes it easy to compose and build very complex UIs, something that got me hooked to Flutter. So, what is a widget?

A widget is simply a class that describes the configuration of an element. An element is an instantiation of a widget at a particular location in the widget tree. For example, a button widget describes the configuration of the button – that it needs to have text, color and a click listener for instance. When that button widget is instantiated and added to the widget tree (let’s say screen for now) it becomes an element that the framework can interact with. One widget can be instantiated in multiple locations in the widget tree creating multiple unique elements. For more information check out the Flutter documentation. In simpler terms, a widget is a description of part of a user interface, for instance, a button, a checkbox or a column.

An important feature of widgets is that they are immutable. There is no such thing as myWidget.setNewProperty(prop) if you want to change the configuration of a widget. All widget properties are final. You will have to build a new widget with the updated configuration if there is a change in configuration.

There are two kinds of widgets in Flutter – stateless widgets and stateful widgets. Let us take a look at what they are and how they are used.

Stateless Widgets

These are widgets that do not require mutable state. They depend on the configuration information in the widget object itself and the BuildContext in which the widget is inflated. These configurations come in form of parameters that are added through the widget’s constructor. Examples of stateless widgets are Text, Image etc. Here is how a stateless widget looks like:

class MyWidget extends StatelessWidget{

const MyWidget({

Key key,

this.myProperty

}): super(key: key);

final String myProperty; // configuration property

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context){

// what the widget will look like on screen

return Center(

child: Text(myProperty),

);

}

}

The build method inside the stateless widget describes the part of the user interface represented by the widget. It is called in one of three situations: the first time the widget is inserted in the widget tree, when the widget’s parent changes its configuration, or when an InheritedWidget it depends on changes. Unless a parent widget’s configuration changes or an InheritedWidget it depends on changes, a stateless widget’s build method will only be called once – when it’s inserted in the tree.

One should use stateless widgets when the data they hold will not change during the lifetime of the widget. If the data is going to change then one should use a StatefulWidget.

Stateful Widgets

These are widgets that hold data that may change during the lifetime of the widget. This data is called State. State is information that can be read synchronously when the widget is built and might change during the lifetime of the widget. Stateful widget instances are immutable and they store their mutable state either in seperate State objects or in objects to which the State subscribes. Examples of stateful widgets are checkboxes and animations. Here is how a stateful widget looks like:

class MyStatefulWidget extends StatefulWidget {

const MyStatefulWidget({Key key, this.myProperty}): super(key: key);

// stateless widgets may have some properties

final String myProperty;

@override

_MyState createState() => _MyState();

}

class _MyState extends State<MyStatefulWidget> {

@override

void initState(){

super.initState();

// initialize your internal state if needed.

}

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Center(

child: Text(

widget.myProperty, // you can access the widget's properties

// through State's widget property

)

);

}

@override

void dispose(){

// release all resources

super.dispose();

}

}

As you can see, a stateful widget does not have a build method. Instead, it has a createState method that the framework calls whenever it inflates the widget. Multiple State objects might be associated with the same StatefulWidget if that widget has been inserted into the tree in multiple places.

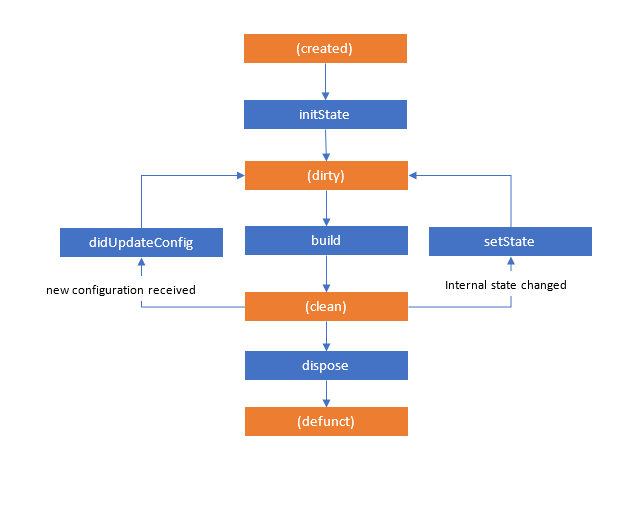

When there is a change in state the build method of the State object is called to reflect the change. This can be triggered when the internal state of the object changes and you call the setState method or when it receives a new configuration through the didUpdateConfig method. Here is a simple lifecycle of the State object:

As you can see in the image above, whenever the State object is ‘dirty’ it has to be rebuilt by calling the build method to reflect the change. StatefulWidgets should be used when the data they hold is likely to change during the lifetime of the widget. One should be careful when working with stateful widgets. When you make a stateful widget the root of your widget tree then whenever its state changes the entire tree will be rebuilt which might have a negative impact on performance. It is therefore advised that you push stateful widgets to the leaves of your widget tree.

Conclusion

In this post we spoke about StatelessWidgets and StatefulWidgets, their differences, and when one should use them. Once again many thanks for taking your time to read.

Comments